LET’S GET EXCITED ABOUT THIS BOOK!

Imagine being told if you ever stepped out of your home you would be shot on sight? Now imagine living 32 years of your life inside a hotel? This is the plight of Count Alexander Rostov in this splendid novel by Amor Towles. After being placed under house arrest by a Bolshevik tribunal in 1922, Count Rostov has no idea what life will have in store for him inside the Metropol hotel in Moscow. But the life that unfolds for the Count is full of friendship, love and purpose. I absolutely loved joining the Count on this unique adventure of his! Read my full review of “A Gentleman in Moscow,” below and let me know your thoughts on this novel in the comments!

Shannon’s Rating — PG-13

LET’S TALK ABOUT THIS BOOK!

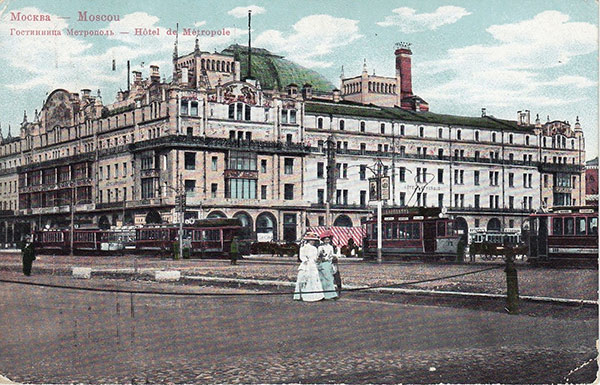

Have you ever dreamed of staying at The Plaza in New York City? I have. Many times. But after reading, “A Gentleman in Moscow,” by Amor Towles, I now dream of staying at the Metropol in Moscow. One day I’m going to take a trip to Moscow (preferably with my book club friends who first read this novel with me.) I’ll book a room in the Metropol and wander it’s halls envisioning my fictional friend, Count Alexander Rostov living there for 32 years!

To say I loved “A Gentleman in Moscow,” is an understatement. It’s one of those novels that completely enchanted me. I loved the writing. I loved the history. I loved the characters. In short, I loved everything about it. The plot of the book is very simple to explain. In 1922, Count Rostov was arrested for writing an inflammatory poem during a tumultuous time in Russian history. He was sentenced by a Bolshevik tribunal to house arrest in the Metropol Hotel and told that if he ever stepped outside of the hotel he would be shot. The Count lives the next 32 years in the attic rooms of the Metropol. Amor Towles once said in an interview that he worried about trapping his hero and his readers inside a single building for that many years and how such a confining environment might stifle the plot. But he soon discovered that “the hotel kept opening up in front of me to reveal more and more aspects of life.” I, personally, didn’t find the confined setting to be stifling at all. In fact, quite the opposite. It was fascinating to see how an endearing, yet selfish, man of leisure evolved over these years of house arrest. Late in his life, the Count was discussing the new, modern inventions of the world and how they supposedly made people’s lives more convenient (things like; dishwashers, toasters, vacuum cleaners and televisions.)

“I’ll tell you what is convenient,” he said after a moment. “To sleep until noon and have someone bring you your breakfast on a tray. To cancel an appointment at the last minute. To keep a carriage waiting at the door of one party, so that on a moment’s notice it can whisk you away to another. To sidestep marriage in your youth and put off having children altogether. These are the greatest conveniences, and at one time, I had them all. But in the end, it has been the inconveniences that have mattered to me most.”

It’s these “inconveniences” that happen in the Count’s life that bring such charm to the novel. We watch the Count learn how to adapt from living a lavish lifestyle to living in the servant quarters of the hotel attic. We watch him befriend Nina, “a young girl with a penchant for yellow,” who is also living in the hotel. We watch him become the headwaiter at the hotel restaurant and learn how to excel at a job for the first time in his life. We watch him fall in love with the beautiful “willowy actress,” Anna. We watch him form genuine friendships with hotel workers, an American diplomatic and even a Bolshevik government official. And, finally, we watch him open his heart to his adopted daughter, Sofia, for whom he risks everything to provide her with a better life.

The structure of “A Gentleman in Moscow” is very unique and being aware of how it is organized before starting the novel will be useful. Here’s how Towles describes it’s format…

“As you may have noted, the book has a somewhat unusual structure. From the day of the Count’s house arrest, the chapters advance by a doubling principal: one day after arrest, two days after, five days, ten days, three weeks, six weeks, three months, six months, one year, two years, four years, eight years, and sixteen years after arrest. At this midpoint, a halving principal is initiated with the narrative leaping to eight years until the Count’s escape, four years until, two years, one year, six months, three months, six weeks, three weeks, ten days, five days, two days, one day and finally, the turn of the revolving door. While odd, this accordion structure seems to suit the story well, as we get a very granular description of the early days of confinement, then we leap across time through eras defined by career, parenthood, and changes in the political landscape; and finally, we get a reversion to urgent granularity as we approach the denouement. As an aside, I think this is very true to life, in that we remember so many events of a single year in our early adulthood, but then suddenly remember an entire decade as a phase of our career or of our lives as parents.”

I really enjoyed this unique novel structure. It’s so very true of life. Some days and weeks seem to drag on forever and yet entire years seem to fly by in a blink of an eye.

Count Rostov appeared to have an idyllic life before his imprisonment. But it wasn’t until his years of confinement that he truly learned to live.

“Since the beginning of storytelling, Death has called on the unwitting. In one tale or another, it arrives quietly in town and takes a room at an inn, or lurks in an alleyway, or lingers in the marketplace, surreptitiously. Then just when the hero has a moment of respite from his daily affairs, Death pays him a visit. This is all well and good, allowed the Count. But what is rarely related is the fact that Life is every bit as devious as Death. It too can wear a hooded coat. It too can slip into town, lurk in an alley, or wait in the back of a tavern…”

Life was indeed devious and snuck up on Count Rostov. His house arrest, which appeared to be a punishment, was in actuality a great blessing. As one of his friends remarked to the Count, “Who would have imagined when you were sentenced to life in the Metropol all those years ago, that you had just become the luckiest man in all of Russia.”

Be warned…the ending of “A Gentleman in Moscow” is somewhat bittersweet. It keeps us guessing a bit. But I’m ok with that. I’m very good at creating happily-ever-after “epilogues” in my brain and giving my own endings to characters and books when needed. If you read this book, let me know and I would love to discuss the ending with you and see if your “epilogue” coincides with mine!

Leave a comment